Turning prayer into deeds

United Methodist Women celebrates its 150th anniversary

by Barbara E. Campbell*

Women of the Methodist, Evangelical, and United Brethren churches – with a growing awareness of the needs of women, children, and youth in the late 1800s – determined they would “do something about it!” They organized woman’s missionary societies. The Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) of the Methodist Episcopal Church was established March 23, 1869, “possibly the most famous rainy day since the flood!”1

The story begins in Boston when eight Methodist women voted to form the first society. The plight of women and children in India, as described by missionary women home with their families for itineration, moved them into action. Within days, the WFMS was formally chartered; within weeks two single women missionaries, Isabella Thoburn, a teacher, and Clara Swain, a medical doctor, were recruited for service. In December 1869 they sailed for India. By the mid-1890s, nine woman’s home and/or foreign missionary societies had been organized in the five denominations that later became The United Methodist Church. They “preached” the gospel by establishing Christian schools, clinics, orphanages, and community centers and by dispatching thousands of missionaries and deaconesses (mostly single women) to five continents. Institutions they founded, such as Isabella Thoburn University (India), Red Bird Mission (KY), and Harford School (Sierra Leone), remain significant mission centers.

Not all mission leaders and pastors were supportive. Women’s assertiveness challenged norms and created anxieties, and there were worries about money. “Parent board” officials questioned the competence of the women while worrying their success might disrupt or subvert mission giving. A mission executive inquired of the WFMS, “Could you ladies make the necessary arrangements for Miss A to go to India, obtain bills of exchange, care for her in sickness and health?” Answering his own question: “No. Your work is to forward the money to New York. We will credit the society and keep you informed.”2 In 1872, when the women of the Church of the United Brethren wanted to organize, “One brother put it, ‘No telling to what lengths they may go; it is ‘a fifth wheel;’ it [the society] is not needed.” A woman replied, “It has been said that the Women’s Missionary Society is a fifth wheel to the wagon. Well, perhaps it is, but we intend to be the driving wheel.”3

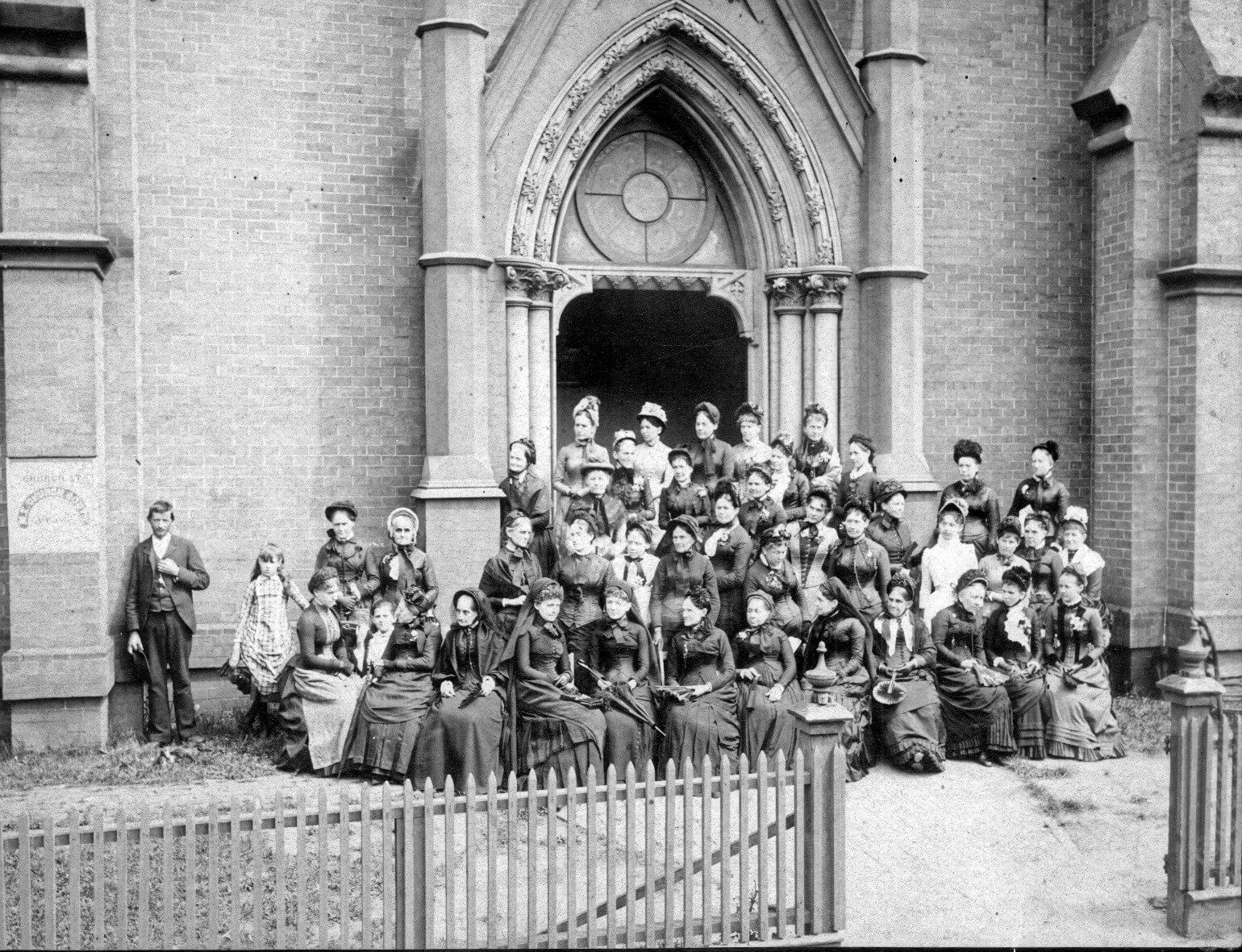

Woman’s Board of Foreign Missions, 1882-1883, MEC, Boston, Massachusetts. PHOTO: GCAH MISSION EDUCATION AND CULTIVATION COLLECTION

Organizing for mission

To accomplish their work, the societies needed a stable support system and a firm financial base. Corresponding secretaries were charged with organizing auxiliaries. Within weeks of the WFMS founding, women in 11 Boston-area churches sent gifts. First year membership reached 26,686 with contributions of $22,379.90. During 1878-79, the Woman’s Board of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, organized 218 local societies in 15 annual conferences. The national president, Mrs. Juliana Hayes, attended 11 of the organizing meetings. The United Brethren Women’s Missionary Association grew from 500 members in 1873 to 3,555 within a decade.

Historian Mary Isham’s description of the WFMS summarizes: “They [the women] were driven to the gleaning of the littles, two cents a week, made vital by prayer, mite box collections, sacrificial gifts, life-memberships – and out of the littles built an income, growing year after year, which made possible an ever growing agency for the spread of the gospel.”4

The nine missionary societies variously named “home,” “foreign,” “woman’s,” and “women’s” shared remarkably similar purpose and organizational patterns: monthly meetings, Bible studies, missionary reports, collections, leaflets, and societies for children, youth, and employed women. The Mother’s Jewels Circle for 5-year-olds sent their collection to the home by that name in York, Nebraska, serving 65 orphans. (Today it serves as Epworth Village.)

The founders understood they needed an educated membership to financially sustain the growing ministries. In its first business meeting, the WFMS authorized “a paper” they called The Heathen Woman’s Friend. (Later renamed Woman’s Missionary Friend.) By year’s end, it was self-supporting with 4,000 subscribers. Later publications in other societies included Woman’s Evangel, The Woman’s Missionary Record, Our Homes, World Outlook, and The Methodist Woman. Today’s response magazine, published by the National Office of United Methodist Women, is the 15th “paper” in an unbroken line.

Church Union: the Methodist Church, 1940

Three Methodist denominations united in 1940 to form The Methodist Church. All “women’s work” was then lodged in the Woman’s Division of Christian Service (WDCS) of the Board of Missions. As leaders of six uniting societies worked toward union, they faced two obstacles: internal disagreement and “subtle” external opposition from clergy. Women fought to retain fiscal authority for their ministries. Would the head of the national organization be a “president” or “chairman?” Only the former title granted legal authority. Women struggled and prayed, acknowledging, “We cannot go farther until we go deeper.”

The (new) WDCS, with a president, had three departments: Home, Foreign, and Christian Social Relations, and a Section on Education and Cultivation. Their work encompassed approximately 700 active missionaries and 700 deaconesses, hundreds of retirees, and hundreds of mission institutions across the United States and in 20 countries. Local Woman’s Societies of Christian Service and Wesleyan Service Guilds provided financial support.

The Evangelical United Brethren Church, 1947

Evangelical Church and the United Brethren in Christ united in 1947 to form the Evangelical United Brethren Church, with local Women’s Societies of World Service. A Woman’s Division (Council) within the Board of Missions did not have administrative responsibility but supported ministries with women and children.

A deaconess opens the Christmas barrel at Erie Home, Olive Hill, Kentucky. PHOTO: GCAH MISC #3, P. 8

The agreements of 1964

Methodist women’s missionary history was transformed by action of the 1964 General Conference upon recommendation of the Board of Missions. It removed and transferred administration of all women’s mission projects, personnel, and selected educational functions to other divisions of the board. There were guarantees for increased board membership for women; enhanced women’s staffing, while “the women” (WDCS) retained control of property and finances, making annual appropriations to the Board of Missions to sustain (pay for) the work they formerly managed. Division staff was reduced from 54 to 14. That year was a very painful time with many unforeseen and far-reaching consequences.

Missionaries and mission work had been the central focus of the women’s societies for almost 100 years, with international relations and social justice issues intertwined. The World Federation of Methodist Women, founded in 1939, was an outgrowth of the WFMS International Department (1929). The first Charter of Racial Policies (1952) expanded work initiated in 1924 by the Woman’s Missionary Council’s Committee on Racial Cooperation.

With a greatly reduced structure and staff, the Women’s Division faced massive rebuilding and program reorientation as it worked toward church union in 1968. All this came as social justice issues and civic unrest roiled the 1960s, 70s, and 80s.

After eight decades, Methodist women could celebrate substantial accomplishments, although tragedy and misfortune were not uncommon. Illness and death were constant realities. Fire destroyed multiple mission structures; two depressions caused financial hardships, reduced appropriations, and stagnant missionary salaries. During World War II, atomic bombs destroyed Hiroshima Girls School and damaged Kwassui Jo Gakuin in Nagasaki. Property in Europe was confiscated. During the Communist Revolution in China and the Korean War, properties were confiscated and missionaries imprisoned. The U.S. military’s firebombing of Manila destroyed Mary Johnston Hospital in 1945. In 1964, Jesse Lee Home in Alaska suffered earthquake damage, which required its relocation.

Sewing Class, Jessie Lee Home in Unalaska, Aleutian Islands, Alaska, 1915. Woman’s Home Missionary Society. PHOTO: General Commission on Archives and History

Church union: The United Methodist Church, 1968

The United Methodist Church was created in 1968 with the union of the Methodist and Evangelical United Brethren churches. Locally, most congregations had a Women’s Society of Christian Service or a Wesleyan Service Guild.

Theressa Hoover was named associate general secretary of the Women’s Division, Board of Missions, in 1968, and later, as the structure changed, the deputy general secretary, the highest position an African-American had achieved in the church at that time. The division program staff gradually increased and Christian Social Relations programs expanded. The newly built Church Center for the United Nations (CCUN), owned by United Methodist Women, offered joint seminars on national and international affairs, provided work space for international “petitioners” seeking United Nations recognition, and became a meeting place for international women. Decades earlier,peace efforts had been strengthened by a division representative attending the U.N. founding (1947), publication of a mission study “We, The People,” and securing U.N. official observer status in 1950.

Dr. Xue Zheng, principal of former Methodist girls’ school in Shanghai, China, with Mai Gray, president of the Women’s Division, and Theressa Hoover, the Women’s Division’s Associate General Secretary, 1980. PHOTO: JOHN GOODWIN/GLOBAL MINISTRIES

The uniting societies refined the local structures and updated terminology. Separate societies for employed women were no longer viable as increasing numbers of women were employed. The division devised new ways of engaging women’s interests. A committee of 24 named in October 1971 to envision a new and different future recommended “One new inclusive organization with a new name – United Methodist Women,” which was approved by General Conference.

United Methodist Women, 1972

General Conference created the General Board of Global Ministries in 1972 with the Women’s Division as one of its seven divisions. This change, simultaneous with the creation of United Methodist Women, required extensive interpretation.

The first trauma of the new organization was the adoption of the “Watergate Statement, 1973,” wildly misunderstood as a call to impeach the President. It was in fact a call to the House of Representatives to begin impeachment proceedings against the President. United Methodist Women’s president, Mrs. C. Clifford (Hazel) Cummings, was berated in-person and by letter, telephone, telegrams, in meetings and at her home. Her sister, who answered the telephone in Hazel’s absence, remarked, “I thought you were part of a Christian organization.”

Program development and inclusiveness efforts took many forms: Spanish and Korean resources, Ethnic women’s seminars, World Understanding Teams, withdrawing investments from South Africa, legislative training events, boycotts, and supporting the Equal Rights Amendment.

Educational efforts accelerated among members of United Methodist Women in Schools of Christian Mission, In-Conference workshops, assemblies, and National Seminars. The division produced annual mission studies—spiritual growth, Bible, and social action texts. The Reading Program expanded.

A third Charter for Racial Justice Polices (1978) was later adopted by General Conference. The Centennial Era (1982-1986) was celebrated in conjunction with Methodism’s 200th anniversary. The “Campaign for Children” was launched in 1988 in cooperation with the Children’s Defense Fund. At times, Women’s Division support of selected social justice issues generated discontent and public attacks from members and outsiders. Local members increasingly participated in local ministries serving women and children.

United Methodist Women, like its predecessors, exists in two interrelated parts: 1. the small corporate body and national staff based in New York City; and 2. the 800,000 members at work in churches. The former handles national and ecumenical administrative tasks, allocates funds, manages mission property, and recommends program emphases.

The sacrificial giving of dedicated members has enabled worldwide mission for 150 years. The dollar value of their volunteer time cannot be calculated. Cumulatively, each woman’s pledge, or gift, plus bazaars, yard sales, and church suppers determine the national budget and support conference and district programs. Far larger amounts help support churches and local programs for women and children. Members engage in study, assemble kits, attend rallies, contact legislators, and work to overcome social injustices.

Participants during an ecumenical workshop on women’s empowerment in Kalay, Myanmar. The workshop was sponsored by the Women’s Department of the Myanmar Council of Churches and led by Emma Cantor (second from left), a regional missionary with United Methodist Women. PHOTO: PAUL JEFFREY

Conference mergers and district realignments negatively impacted United Methodist Women. Conference leaders serve greatly enlarged areas with increased travel time and expense. Travel time to meetings can exceed program time, discouraging attendance. Reduced numbers of conferences and districts reduces leadership opportunities.

A Separate Agency

Membership decline in United Methodist Women parallels that of the church. Many older women are less willing to accept the stresses of office-holding. Younger women

seek informal styles of organization, infrequent meetings, and hands-on, short-term projects. Changing demographics, the increasing impact of social media, and restlessness within the denomination present new challenges. Membership interests have become increasingly local.

The 2012 General Conference granted approval for United Methodist Women to (again) become a separate agency while remaining “missionally connected” to the General Board of Global Ministries, exchanging memberships and sharing projects. Many pre-1964 program functions were returned to United Methodist Women, although the context of mission has greatly changed.

Leadership development, mission education, spiritual enrichment, and informed giving are hallmarks of the decades. Building on the past, the organization has adopted flexible structures, prioritized advocacy on behalf of critical social issues, offered Ubuntu travel experiences, and provided social media platforms.

For 150 years, United Methodist Women has worked for women and with women to share the gospel and overcome barriers. In the late 1800s, Isabella Thoburn reportedly said, “No people ever rise higher than the point to which they elevate their women.” Over a century later (2005), the United Nations Millennial Goals highlighted the low status of the world’s women.

In the 21st century, women still need to organize for mission!

*Barbara E. Campbell is a retired deaconess and former Women’s Division’s staff member, Global Ministries.

Notes

1Mary Isham, “Valorous Ventures: A Record of Sixty and Six Years of the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society, Methodist Episcopal Church,” WFMS Publication Office, Boston, 1936, p. 13.

2 Ibid, p. 16.

3 Betty J. Letzig, “National Mission Resources,” Mission Education and Cultivation Program, General Board of Global Ministries, 1987, p. 7.

4 Isham, Ibid, p. 29.

Copyright New World Outlook magazine, Fall 2018 issue. Used by permission. Email the New World Outlook editor for more information.